By Janet (Krider) Duncan ‘58

Manhattan experienced large growth and change after the civil war. Many people suffered from the hard times of what was know as the Panic of 1873. An average of only two out of three children attended school on any given day for an average of five months a year. In 1870-1871, 69 students were reported in the District’s high school while the newspaper gave 100 students at the high school picnic in 1871. Even the lower number was too many students for the upper room of the 1857 Avenue School. All the schools in town were crowded: in the two primaries, Amanda Arnold had 56 students and Mrs. McBride had 65; Miss Robinson’s secondary class had 62; and Miss White’s Grammar school grades had 60 children on the first floor of The Avenue School. In 1873, the School Board asked for new buildings. But the voters of Manhattan said No.

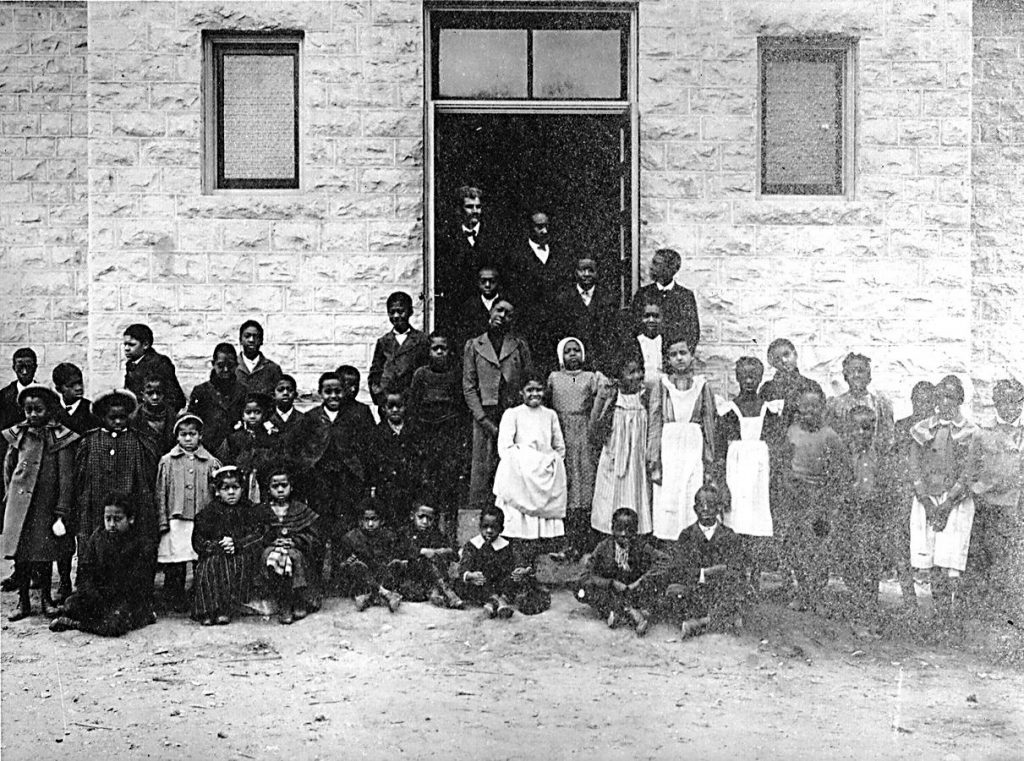

Until this time, all children, black and white, were educated in “the same apartments,” in the same school building if not in the same classes. To make more room, the Board then voted to: ”sustain a school for the colored population in a separate building,” The children and their teacher, Mr Stewart, were given a room in the “colored church.” The students from the high school visited them in November of ’73. As they reported in their newspaper, they found “22 scholars and as many classes.”

In December, the new school was referred to as the “Manhattan Colored Institute” and reported 25 scholars. The Institute formed a ‘Base Ball Club’ and extended a “cordial invitation to the young people of the city and vicinity” to play. They hoped to “effect a better state of feeling between the Institute and our sister schools.” Perhaps this tells us something about the ages of the colored students at the Institute. Manhattan High School formed their baseball team in 1873 also – did they play each other? These and other questions will require more research.

Manhattan’s population, both white and black, continued to grow rapidly, creating more construction than the town had seen in years. By 1875, Manhattan’s black population had reached 100, a now visible number and a doubling in percentage (to 6%.) An editorial in The Nationalist newspaper condemned the growing segregationalist policies. “Color Prejudice,” they wrote, is “warping … to the mind of the possessor…. In spite of the building boom, the hard economic situation continued for many people and an Aid Society was formed to help the destitute. The high school helped by putting on a variety show which featured ‘the grave and comic’ in several acts and skits. All the ticket proceeds went to the relief effort.

In 1878, the School Board was finally successful and voters passed the bond for building the Central School on Leavenworth at Juliette. Manhattan High School now moved into modern quarters in the new building.

Then, during 1879-1880, 104 poor freed black men, women and families arrived by train in Manhattan from the south. Helped by several in Manhattan, but not welcomed by many others, these Exodusters were left here (and in other towns across Kansas) with next to nothing. The Manhattan Citizen’s Committee formed to deal with the situation did not remember the editorial of 1875. They reported it “would be untrue to our former history…if we did not extend a cordial welcome to the colored refugees,” but at the same time they felt somehow the whole thing was a Democrat vs Republican scheme and that the “colored people would be more happy and prosperous in the south than in the north.” Many stayed, wanting only freedom and a job. By 1880, the city’s black population reached 15%. Before this there had been no defined housing area in town . After 1880, neighborhoods began to be segregated.

In 1882, the School District was successful with another Bond and the new Avenue School was built. And with the new space available, the Board moved the black classes into Central School. Reports show black children in classes there in 1884, in their own rooms with their own Principal (who has been referred to with respect to high school in other references, but as was said before, more research is needed here) and teacher. A third teacher, Eli Freeman, was added in 1886 for grades 1-3.

The population of the city by 1885 was estimated to be 2,100, and Dr J. W. Evans reported that “most of town west of Juliette was prairie.” Dr Evans went to Central School, then moved to the Avenue School for grammar school, graduating from 8th grade there. Dr. Evans then went directly from 8th grade to Kansas State Agricultural College by passing the College entrance examination, graduating from KSAC in 1894 at the age of 19.

The “The School Bulletin,” printed in the District in 1889 reported on current health issues affecting Manhattan school children. The national economic situation was never far from Manhattan’s main street, and the Bulletin printed articles with opinions ranging from Wall Street “trusts” as “an evil of our time” to the problematic use of having only one out-house in a school yard. (“Parents think of your daughters being obliged to go to such places in common with rude and vulgar boys!”)

Manhattan’s population in 1890 reached 3,014. The July 4th, 1891 celebrations in Sarber Grove (roughly Staple’s-Hasting’s area, which would then have been on the other side of the Blue River) were attended by over 1000 people. Patriotism, idealism and the fun of the Fourth of July were all present in abundance. While times were still difficult in many ways, a newspaper reported that most of the people from the rural areas arrived in buggies and carriages their grandparents would have considered “extravagant a mere 50 years ago.” On the other hand, they noted that the patriotic speeches quickly turned to themes of foreclosure and poverty even as they spoke to the well-fed and well dressed crowd.

So it was between “well-fed” and “foreclosure” that the School Board faced the looming “High School Question” we left at the end of our History Part I. The School Board presented their position in their Annual Report. District Superintendent W. I. Whaley stated that he found very few records before 1887 – not even the names of High School graduates. (While we read in a later history that there were no high school graduates until 1892, maybe there were graduates but this lack of records has left them unrecorded.)

Their goal was to have the best schools in the state by: increasing attendance, decreasing tardiness, and showing rapid progress in pupil learning. These words avoided several big problems, however, and they all revolved around money. Not least was an embezzlement of funds by the ex-Riley county treasurer, which had caused them a “serious and embarrassing financial blow.” They still had the Central School bonds of $15,000 (at 10% interest) and the Avenue School bonds for $10,000 (at 6%) to repay. There was also a legal question of the Board’s right to collect taxes from the landowners in Pottawatomie County whose children attended the District Schools. And there was a problem of lack of heat at Central School (which included MHS) where it got so cold in winter that “students and teachers alike wore coats and hats” and they sometimes even dismissed school.

But worst of all, in spite of the general population increase in the district, there was a loss of students. The census count in 1890 showed 139 fewer children for ages 5-21 than had been counted in 1888. And attendance was at an average of 52% in 1885, an all-time low. The Board made the decision “to reduce teachers by at least one and return the basement room of the High School to the Grange store room.” To do this, they had “either to discontinue the High School or the Colored Room.”

Both the high school and the “Colored Room” had low student numbers. The “Colored Room” was now under one teacher, Mr. Freeman. But in the high school, it was proving impossible to keep a Principal (the teacher.) The 1889 high school Principal had had a “very

good second year, with 38 students,” (down considerably from twenty years earlier.) Then he quit. A difficulty, the Board reported, of “hiring for one year and not paying well.” High school enrollment dropped from there. A new principal, Miss Mary Swaney, was hired but after only three months she was “called to South America.” Still in dire financial straits, the Board persuaded Professor James Lee (former KSAC Professor and District Superintendent) to return to finish the remaining six weeks of the term.

The College policies would have influenced the School Board, too, with its Preparatory Department and its early-admission policy. Figures for the Prep Department at KSAC for the years 1896-1901 show a steady growth from 67 to 318 students. (A breakdown by class is not given.)

The Board felt it was time to discontinue Manhattan High School. Public outcry was the result. The colored class of Mr. Freeman was dropped instead. This time the 30 or so students were apparently dispersed among the other classes. For the high school, after much effort, Miss Amy Gerrans was hired as the principal. (This frequent change of teachers was deemed an ‘evil’ and ‘detrimental thing.’)

Amid this upheaval in the high school, the Board proposed other changes that are with us today: that schools should be named, and that the school year be organized into terms of nine months instead of the previous eight. For the high school, two courses of study were adopted: a two-year English course which, upon completion, admitted the graduate to the second year at KSAC, and a three year course where half was taught in Latin. And the report mentioned that the standards at the College had been raised, which they hoped might help Manhattan High School attendance.

One black student who attended Manhattan schools from 1886 and probably graduated from Manhattan High in 1896 was Minnie Howell. She entered KSAC in September 1896 and was the first black woman to graduate from the College in 1901. She was mentioned in articles in the Manhattan newspapers for her participation in musical recitals, College organizations, and literary societies.

Although the black population in Manhattan had declined slightly from the 1885 high by the end of the century, pressure began for a separate black school. Petitions were circulated among the constituent neighborhoods. In 1903, Eli Freeman wrote a letter to the newspaper stating the case for a “colored school with colored teachers.” Not everyone in their community was supportive of this segregated idea, however, with some believing “it was but to give Mr. Freeman a job and somebody got a pile of money!”

The School Board approved the presentation of the proposal for a two- room school house on the second call of the motion. The Douglas School (original spelling) was opened Jan. 4, 1904. Mr. Freeman was hired as the teacher with 60 students enrolled for the first term. A second teacher was hired in June of 1904. This original Douglas School house, reportedly not finely finished on the inside, was replaced in 1936 by the building standing today. It was built by the WPA with four classrooms, a stage, a principal’s office, toilet and kitchen facilities and a basement. All have wood floors and heat. The school opened in 1937.

By 1900, even without the black students, Manhattan’s population had grown to 4,684 and more school room was needed. East and west wings were added to Central School in 1906 and photos of that era show it without its original big clock tower. City water was brought in and the School Board was proud of the school’s large library. Manhattan High School would now have had quite modern facilities. The 1908 MHS Girls Basketball team shown in a previous Alumni Mentor would have represented MHS from this Central School.

For football, MHS played their games on what was then the empty city- owned Public Square at Bluemont and Juliette, now filled with Bluemont Elementary School. When Bluemont was built in 1911-12, football, both MHS and KSAC, moved to the KSAC field, which would become Memorial Stadium after WWI. Stay tuned while we hit the records to find out when MHS first started playing football and basketball. (We have a photo of the 1908 MHS Girls’ Basketball team.)

In 1909 the College finally made the decision to close its Prep courses. This change, and Manhattan’s continuing growth, was reflected in MHS as Manhattan was a one high school town again. But not for long: Sacred Heart Academy began its high school curriculum in 1911, graduating its first student in 1912.

In 1913, Manhattan high school, with a total enrollment of 340 students, graduated its first students to complete a four year course. And in 1913, the School Board took the next big step. They authorized a new four year Senior High to be built on the site of the Avenue School on Poyntz. At the same time, they authorized a two year Jr. High School. Each building was to accommodate 450 students. Manhattan Senior High School moved into beautiful new quarters in 1914.

The Junior High was ready in 1918. Both of these large school buildings were built on time and within budget – and all of this was during wartime. Construction began on Camp Funston at Ft Riley in July of 1917, which would have a capacity to train over 50,000 troops for WWI. The 1918 Flu epidemic started there in March of 1918. As many as 675,000 people are estimated to have died in the U.S. and Manhattan’s Jessie Lee Foveaux gives a vivid description of the local scene in her book, Any Given Day.

Manhattan’s school-building continued into the 1920s with a flurry of construction activity. Theodore Roosevelt Elementary School was built in ‘24. Also in 1924, an Annex was authorized for the Jr. and Sr. High School, which resulted in their Auditorium, seating 1,070, with its gym behind the stage. Additional classrooms for shops, vocational agriculture rooms and storage were included. This addition was ready in 1926. Central School was demolished in 1926 and Woodrow Wilson was built in its place.

Also in 1926, the Grand Army of the Republic, a Civil War veterans’ organization, requested that the School Board name the high school in honor of Abraham Lincoln. The group had suggested naming Bluemont Elementary for the Civil War President when it was built in 1911, but this had failed. This time the motion was unanimously passed. In 1927, “Lincoln High School” was carved above the north Entrance to the school auditorium. When you visit The MHSAA Alumni Center, please have a look – you can see it from the glass walkway that now connects the two MHS East Campus buildings.

Fifty great years of MHS history to go!